Chemical and electrochemical reversibility

Last updated: May 21, 2018

My research has started involving various forms of reversibility and asymmetry in electrochemistry. In my quest to make sense of it all, I developed cyclic voltammetry simulations to help me better understand these concepts. As I was reading more about these topics, I encountered this page, in which the author states:

“The term ‘reversible’ is probably the most confusing, misused, and ambiguous term in all of electrochemistry.”

I hope to change this with this tutorial. In this post, I’ll explain three different types of reversibility encountered in electrochemistry:

- Chemical reversibility: The product of electrochemical reaction returns to the original reactant upon a reverse scan instead of a side product

- Electrochemical reversibility: Charge transfer is fast relative to mass transfer

- Practical reversibility: Some property (e.g. structure) is cycleable

My sources include:

- Richard Kelly, “Reversibility – Chemical vs. Electrochemical”

- Mary Louie, Ph.D. thesis, Appendix A.1

- Bard & Faulkner, 2nd edition, chapters 2, 3, and 6

Background

We consider the following system of reactions:

\[O + e^- \overset{k_f}{\underset{k_b}{\rightleftarrows}} R \overset{k_c}{\rightarrow} Z\]This system is an electrochemical redox reaction in which the product can further react in a first-order chemical reaction, commonly called an “$ EC $” mechanism. For more details, check out the fundamentals page.

Chemical reversibility

Chemical reversibility occurs when the product of electrochemically generated species can further react in a subsequent chemical reaction. A reaction with net charge transfer is considered electrochemical, while a reaction with no net charge transfer is considered chemical. The rate of electrochemical reactions is controlled by the applied potential, which is not the case for chemical reactions.

For the $ EC $ mechanism previously considered:

\[O + e^- \overset{k_f}{\underset{k_b}{\rightleftarrows}} R \overset{k_c}{\rightarrow} Z\]The instantaneous rate of $ R \rightarrow O $ at time $ t $, in $\text{mol/s} $, is given by the backwards electrochemical reaction:

\[r_b = A k_b C_R(x=0,t)\]Here, $ A $ represents the electrode area, and $ x = 0 $ represents the electrode surface, which is the site of charge transfer.

The instantaneous rate of $ R \rightarrow Z $ at time $ t $, in $\text{mol/s} $, is given by the first-order chemical reaction:

\[r_{c} = V k_c C_R(t)\]Here, $ V $ represents the total solution volume. $ R $ can react to form $ Z $ throughout the solution volume, not just at the surface.

This reaction is chemically irreversible if:

\[\int_{t=0}^{t=t_{final}} r_{c}(t) dt > > \int_{t=0}^{t=t_{final}} r_b(t) dt\]meaning much more $ R $ turns into $ Z $ than into $ O $ over the course of the experiment. The $ A $ and $ V $ factors in $ r_b $ and $ r_{c} $ illustrate how the cell geometry can influence the extent of chemical irreversibility.

For an $ EC $ mechanism with a first-order chemical reaction, the degree of chemical irreversibility is controlled by the extent of the chemical reaction. The extent of the chemical reaction, in turn, is controlled by the rate constant of the chemical reaction, $ k_c $, and the timescale of the experiment, or $ t_k $. Bard and Faulkner (pg 790) define $ t_k $ as the “characteristic experimental timescale”; for a cyclic voltammetry experiment running from an initial voltage $ V_i $, to a final voltage $ V_f $, and back to $ V_i $ with a scan rate of $ \nu $, $ t_k = 2(V_i - V_f)/\nu $. Thus, the “dimensionless kinetic parameter” (pg 797) that controls the degree of chemical irreversibility is given by:

\[k_c t_k\]Intuitively, both a high reaction rate constant and long experimental durations will increase the extent of chemical irreversibility.

Here’s a “sneak preview” of the effect of increasing $ k_c $ on a system:

Electrochemical reversibility

To understand electrochemical reversibility, we should start with the Butler-Volmer kinetic equations:

\[k_f = k^0 \exp\left({-\alpha f (E - E^{0'})}\right)\] \[k_b = k^0 \exp\left({(1-\alpha) f (E - E^{0'})}\right)\]These equations play a key role in defining three key electrochemical concepts:

- Electrochemical facility is defined by the magnitude of $ k^0 $

- Electrochemical reversibility is defined by the ratio of charge transfer ($ k^0 $) to mass transfer ($ (Dfv)^{0.5} $).

- Electrochemical asymmetry is defined by the difference of $ \alpha $ from 0.5

We’ll look at each of these in detail in the following sections.

Electrochemical facility

Electrochemical facility is defined by the standard (heterogeneous) rate constant, $ k^0 $. I like Bard and Faulkner’s definition of electrochemical facility (pg 96):

The physical interpretation of $ k^0 $ is straightforward. It simply is a measure of the kinetic facility of a redox couple.

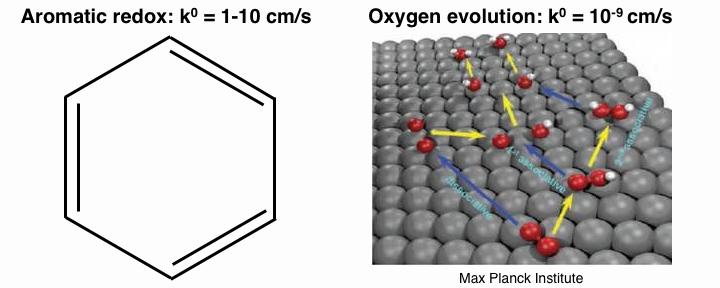

In other words, electrochemical facility is a measure of the ease of electron exchange. The units of $ k^0 $ are $ \text{cm/s} $. Electrochemically facile reactions have values of $ k^0 $ near $ \text{1-10 cm/s} $, while electrochemically infacile reactions have values of $ k^0 $ near $ \text{10}^{-9} \text{cm/s} $. For example, the $ \pi $ orbitals of aromatic hydrocarbons allow for facile electron exchange, while complex, multistep reactions such as oxygen evolution are sluggish.

Electrochemical reversibility

A major confusion I encountered in this understanding is the difference between electrochemical facility and electrochemical reversibility. Kelly’s tutorial gives the following ranges for electrochemical reversibility:

\[\text{Reversible: } k^0 > 0.020 \text{ cm/s}\] \[\text{Quasi-reversible: } 0.02 > k^0 > 5*10^{-5} \text{ cm/s}\] \[\text{Irreversible: } k^0 < 5*10^{-5} \text{ cm/s}\]At first glance, these definitions seem reasonable. Unfortunately, this is wrong - electrochemical facility is not equivalant to electrochemical reversibility! Electrochemical reversibility is formally defined as the ratio of charge transfer to mass transfer, and mass transfer is dependent on the scan rate. Thus, $ k^0 $ is not sufficient to define electrochemical reversibility. If there’s one takeaway I want you to take from this post, it’s this point. Unfortunately, Kelly gets it wrong in his otherwise excellent tutorial.

Cutting through this confusion is a job for Bard and Faulkner (see section 6.4). They define an electrochemical reverisibility parameter, $ \Lambda $:

\[\Lambda = \frac{k^0}{(Dfv)^{0.5}}\]Translating this equation, $ \Lambda $ is simply the ratio of the rates of charge transfer, represented by $ k^0 $, to mass transfer, represented by $ (Dfv)^{0.5} $. Bard and Faulkner give the following ranges for $ \Lambda $ (pg 239):

\[\text{Reversible: } \Lambda \geq 15\] \[\text{Quasi-reversible: } 15 \geq \Lambda \geq 10^{-2(1+\alpha)}\] \[\text{Irreversible: } \Lambda \leq 10^{-2(1+\alpha)}\]For $ k_{c} = 0 $ and $ \alpha = 0.5 $, we can observe the current-voltage behavior of these three regimes:

Electrochemically reversible reactions yield the characteristic “duck curve”, with peaks of similar magnitude on both the forward and reverse scans. These reactions are limited by charge transfer before the current peak and mass transfer after the peak. In contrast, electrochemically irreversible reactions are entirely limited by charge transfer, and thus the observed current-voltage behavior reduces to the Butler-Volmer equation. The currents are identical in both scan directions since the Butler-Volmer equation defines a current for a set overpotential. Electrochemically quasi-reversible reactions display odd-looking intermediate regimes.

One important point is that electrochemical reversibility is a key definition, as the classification of a system as electrochemically reversible, electrochemically quasi-reversible, or electrochemically irreversible has distinct meaning in electrochemistry. Standard relationships between current and scan rate have been developed to extract various parameters from cyclic voltammetry experiments, but these relationships are specific to each domain of electrochemical reversibility. See chapter 6 of Bard and Faulkner or Section IV of this application note from Bio-logic for more information.

Electrochemical asymmetry

Electrochemical symmetry is defined by $ \alpha $, the charge-transfer coefficient. The charge transfer coefficient defines the symmetry of the overpotential in the forward and reverse directions. A reaction is electrochemically symmetric if $ \alpha = 0.5 $ and electrochemically asymmetric if $ \alpha $ deviates from $ 0.5 $.

We can study the effect of the charge-transfer coefficient in the below plots ($ k_c = 0 $):

In the electrochemical reversible limit, the charge-transfer kinetics are so fast that a change in $ \alpha $ is not sufficient to introduce charge-transfer limitations. In the electrochemically irreversible case, we approach the ideal diode limit of the Butler-Volmer equation under forward ($ \alpha = 0.9 $) and backwards ($ \alpha = 0.1 $) bias cases.

Combining chemical and electrochemical irreversibility

We can see the interplay between chemical and electrochemical reversibility in the below plots:

In the electrochemically reversible case, a high $ k_{c} $ can drive the device performance far away from the “duck curve” since the chemical reaction reduces the $ R $ available for the reverse electrochemical reaction back to $ O $. In the electrochemically irreversible case, however, $ O $ slowly converts to $ R $, and $ R $ slowly converts back to $ O $. If $ k_{c} $ is large, nearly all $ R $ will convert to $ Z $.

“Practical” reversibility

Part of my initial confusion with the term “reversible” is my background in batteries - a device that we typically consider reversible. We need a term to describe this type of reversibility, since it’s so common in electrochemistry and so easily confused with other types of reversibility. Most battery materials are “reversible” even if cycled in the electrochemically irreversible regime (fast (dis)charging rates). Bard and Faulkner designate this type of reversibility as practical reversibility. They say:

Practical reversibility is not an absolute term; it includes certain atttitudes and expectations an observer has toward the process.

I see practical reversibility as a catch-all term for electrochemical materials, processes and devices that we we intuitively expect to operate, such as batteries (specifically, battery electrode materials). I propose that practical reversibility is similar to cycleability. This definition is in the context of bulk material changes, not side reactions (since side reactions represent chemical irreversibility).

I hope this tutorial was helpful. Please reach out with any questions, comments, or suggestions!