Paper published: Pulse-induced activation of LFP

I recently coauthored a paper entitled “Beyond Constant Current: Origin of Pulse-Induced Activation in Phase-Transforming Battery Electrodes”, led by my friends Dean and Norman in the Chueh group. It’s been a long road—we collected much of the data for this paper in 2016—but I’m excited to finally see it published.

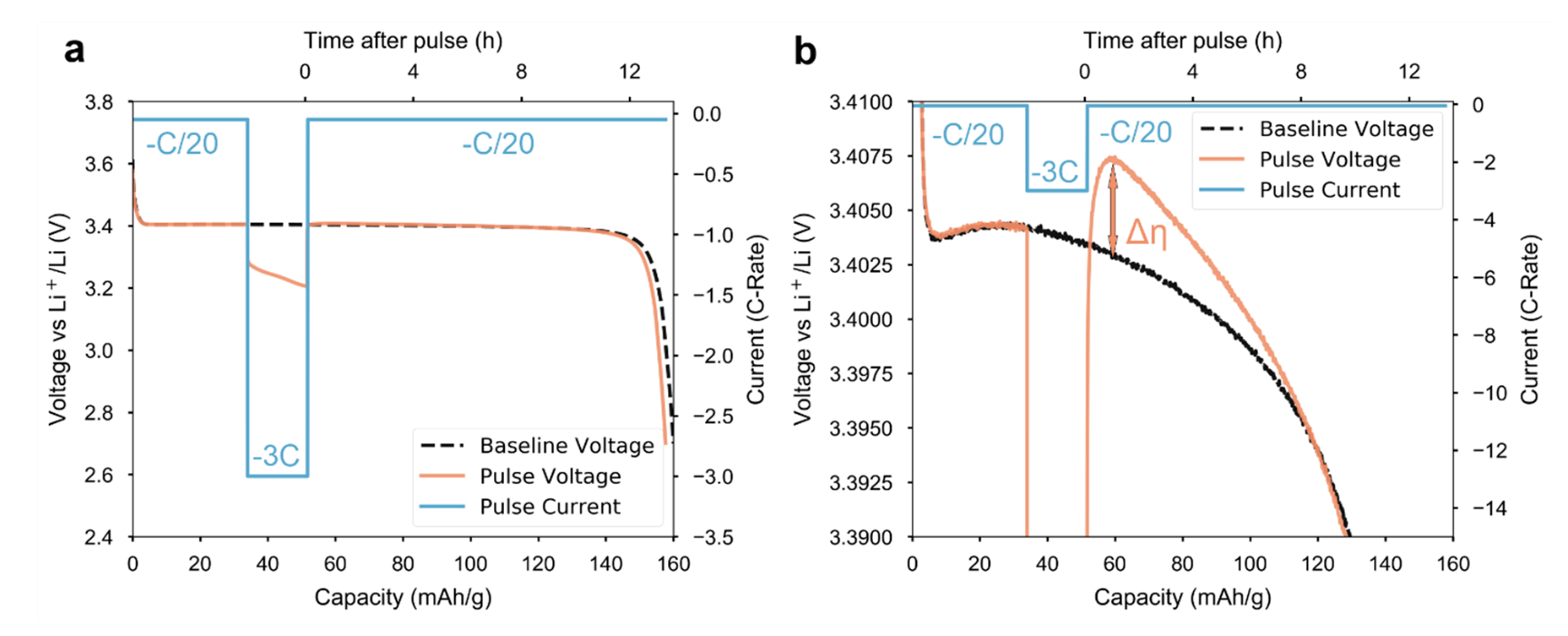

This paper explores an exciting and surprising phenomenon in LFP (which has had quite the resurgence since 2016!). Typically, electrochemical materials exhibit lower overpotential at lower (dis)charging rate. However, upon application of a “pulse” at high rate that interrupts a low-rate cycle, LFP exhibits lower overpotential than it did prior to the pulse:

Lower overpotential means that the battery can (dis)charge more efficiently (i.e., faster and with less energy lost as heat).

This result implies that somehow, the high-rate pulse “activates” the electrode so that it can better support the increased current. Moreover, this activation persists even after the pulse is over.

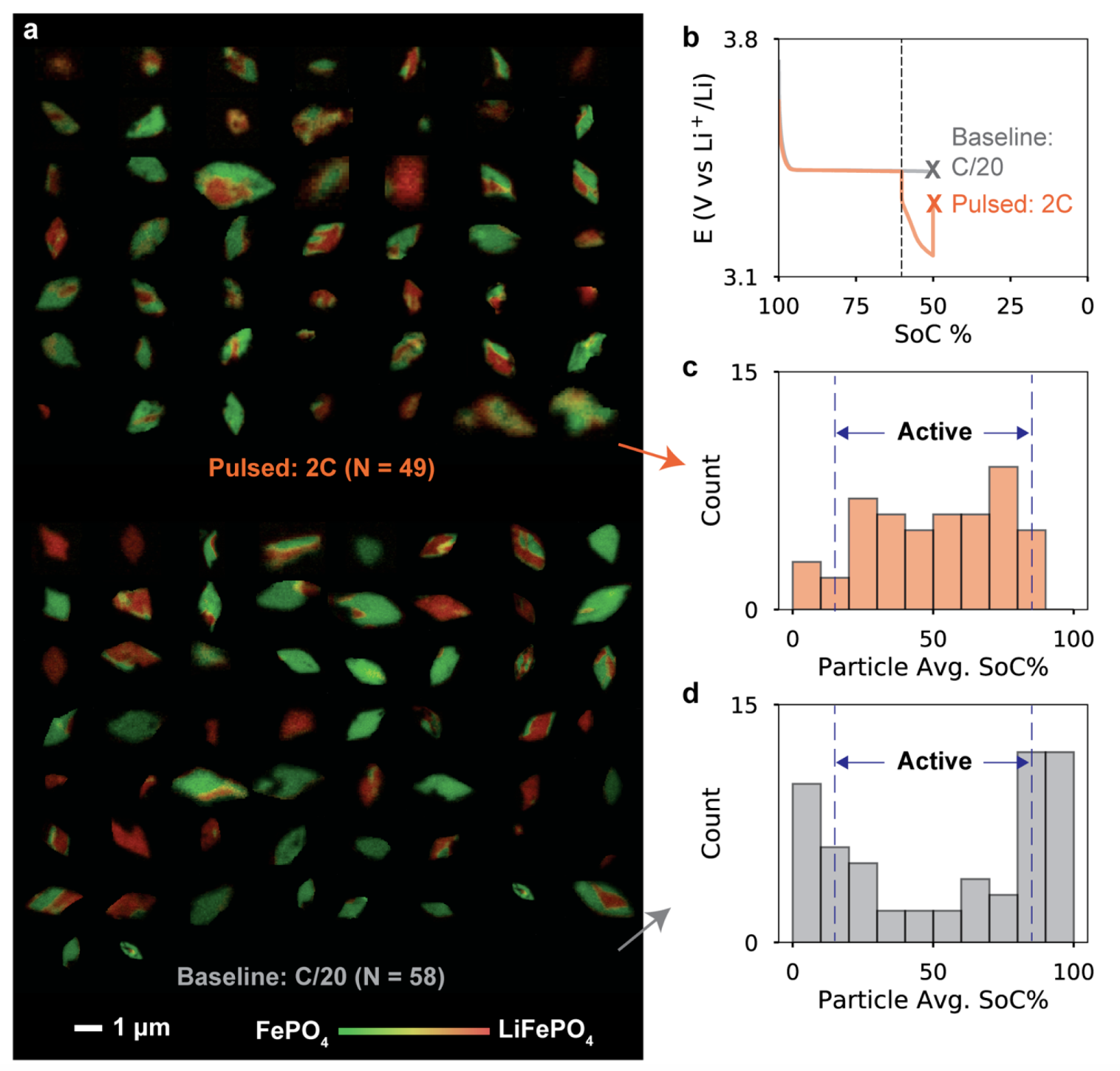

The rest of the paper explains the origins of the phenomenon. A number of effects are at play, but one of the simplest, most important, and most interesting is that the “active particle fraction” (APF) increases upon application of the pulse. The APF represents the fraction of particles that are “active”, where “active” refers to actively (dis)charging lithium (as opposed to at rest). Over the course of a few 24-hours shifts at the Advanced Light Source at LBNL, we observed this behavior via particle-level X-ray imaging:

In short, the high-current pulse activates more particles than were previously active to support the load. When the applied current returns to the slower rate, the larger number of active particles translates to lower current per particle—and thus lower overpotential and more efficient (dis)charging.

I think this paper is a great example of how subtle theoretical phenomona can have outsize implications for the real world. To quote the paper (emphasis mine):

The practical implications of this effect are also significant: heuristics using voltage measurement to determine state-of-charge or state-of-health should account for the possible effects of past current pulses. Likewise, battery management systems can exploit this effect to offer faster battery charging and discharging to consumers. For example, following a burst of regenerative braking current, an electric vehicle can charge more quickly than anticipated due to pulse activation. While it is possible that applying these high current pulses repeatedly to the electrode could cause accelerated degradation, since these high overpotentials will also induce a solid solution in LFP particles, the pulse will reduce the amount of material experiencing interfacial strain. This should mitigate potential damage to the particles during pulse cycling. We also believe that the observed kinetic stabilization of high SSF and APF under transient conditions is a key factor explaining the fast kinetics of LFP in practical use.